What is the Spin-Statistics Theorem?

A Non-Technical Guide to Why Rotation, Symmetry, and the Pauli Exclusion Principle Govern Our Universe.

Article #7 in Quantum Field Theory series.Why is the floor beneath you solid? Why doesn't the Earth collapse into a single point of light? Why does chemistry exist at all?

The answer comes down to two words: ‘Spin’ and ‘Statistics’. To understand them, we will need to examine the social behaviour of particles. As surprising as it may seem, even particles have introverted and extroverted characters.

But first, you need to unlearn everything you thought you knew about 'spinning' objects. It’s time to look deeper.

Rethinking Spin

I might do a full fledged article on this topic someday. Right now, I'll just give you the main idea of what it means in quantum physics.‘Spin’ is a misleading name for a quantum property. It doesn’t refer to the rotation of a tiny ball in a physical space. If an electron had to spin like a top to generate its magnetic properties, its surface would have to move faster than the speed of light, a physical impossibility that would cause the particle to fly apart.

Instead, spin is an intrinsic property, as fundamental to a particle as its mass or electric charge. Think of it not as a motion, but as a signature that tells you how a particle reacts when you rotate the world around it.

To visualize this, imagine rotating different objects in your mind:

A simple arrow: Rotate it 360° (a full turn), and it looks exactly as it did before. Mathematically, we represent it by a vector. They have integer spin (0, 1, 2…)

Arrow on a Mobius Strip: It requires two full turns (720° rotation) to return to its initial state. You can visualize this using the Dirac Belt trick, as demonstrated in the video below.

Mathematically, we represent it by a spinor, the exotic species I introduced in the last article. They have half-integer spin (1/2, 3/2...).

When you rotate a spinor by 360°, its quantum state picks up a “minus sign”, effectively flipping its orientation in a way our eyes can’t see, but the math can feel. Giving it another 360° turn picks up another minus sign, and the effect of two negatives is a positive. Hence, the spinor returns to its original state.

This fundamental difference in how particles perceive a rotation is the doorway to everything that follows. It is the first hint that the universe treats these two groups of particles by a completely different set of rules.

The Mystery of Identical Particles

In our everyday world, no two things are truly identical. If you have two apples that look exactly alike, you could still mark one with a tiny dot of ink, or watch them closely enough to see which is which as you move them around.

Quantum objects, on the contrary, are indistinguishable. There is no “hidden mark” you can put on an electron, and there is no way to track their individual paths with perfect certainty. If you have two electrons and close your eyes for a split second while they interact, there is no physical way to know which is which when you look back.

In QFT, only one electron field is permeating the universe. The field is the ocean. The electrons are water waves. Since every wave is made of the same “water”, there is no way to tell them apart.

Because these particles are identical, swapping their positions shouldn’t change the physical reality of the system. However, in quantum mechanics, the wavefunction (the mathematical description of the particles) has a choice in how it reacts to this swap. When you exchange two identical particles, the universe allows only two mathematical outcomes:

Symmetric: The wavefunction stays the same. (1 × 1 = 1)

Antisymmetric: The wavefunction flips its sign. (1 × -1 = -1)

This might seem like a mere accounting trick. After all, if you square both 1 and -1, you get the same positive result, which represents the probability of finding the particles there. So you may argue that spinors are boring particles without any distinctive features. That’s not true, however.

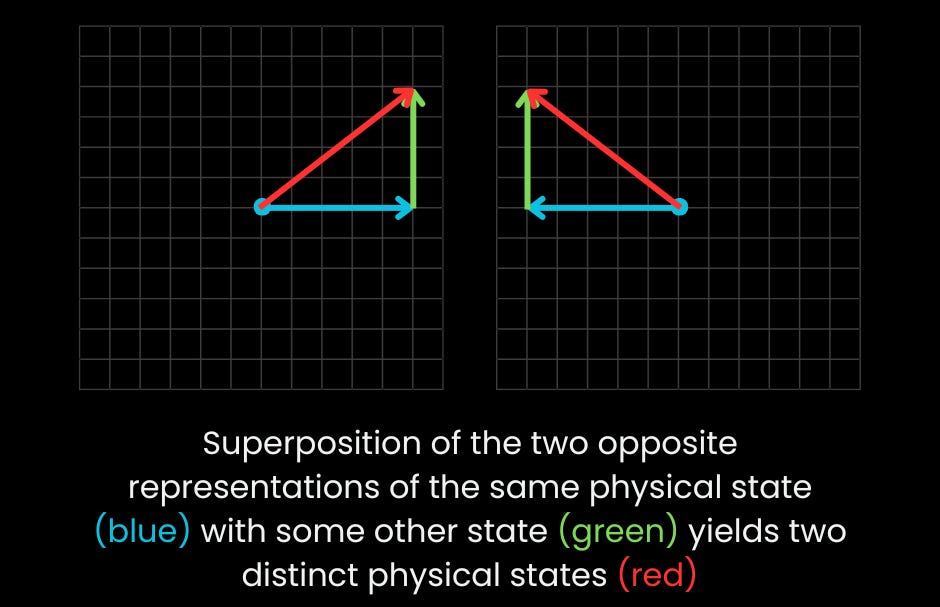

Look at the diagram above. The blue arrows are two opposite representations (+1 and -1) of the same physical state. Now, if we consider their superposition with some other state (green), the resultants (red) will not represent the same physical states. The values of their squares (and hence those of the physical observables like the probability of their position) will be different. This shows that spinors do have interesting properties.

So that “minus sign” is the reason why some particles are happy to pile on top of each other, while others refuse to even occupy the same “room.”

I hope you are enjoying this article. I’m a student and I write these every week for you. They are free to read, but they cost me some precious time. Still I continue to serve you because I believe science should be no secret. If you would like to thank me for my efforts, consider gifting me a donation below:

You can subscribe for free right now.

If you did, then thank you from the bottom of my heart.

I bought a new book with your donations!

My writing skills in the upcoming weeks:

Okay, okay, back to the topic!

The Marriage of Spin and Statistics

Now we come to the central rule of the subatomic world:

A particle’s spin dictates its statistics.

Depending on their exchange behavior (symmetric or antisymmetric), particles fall into two social classes:

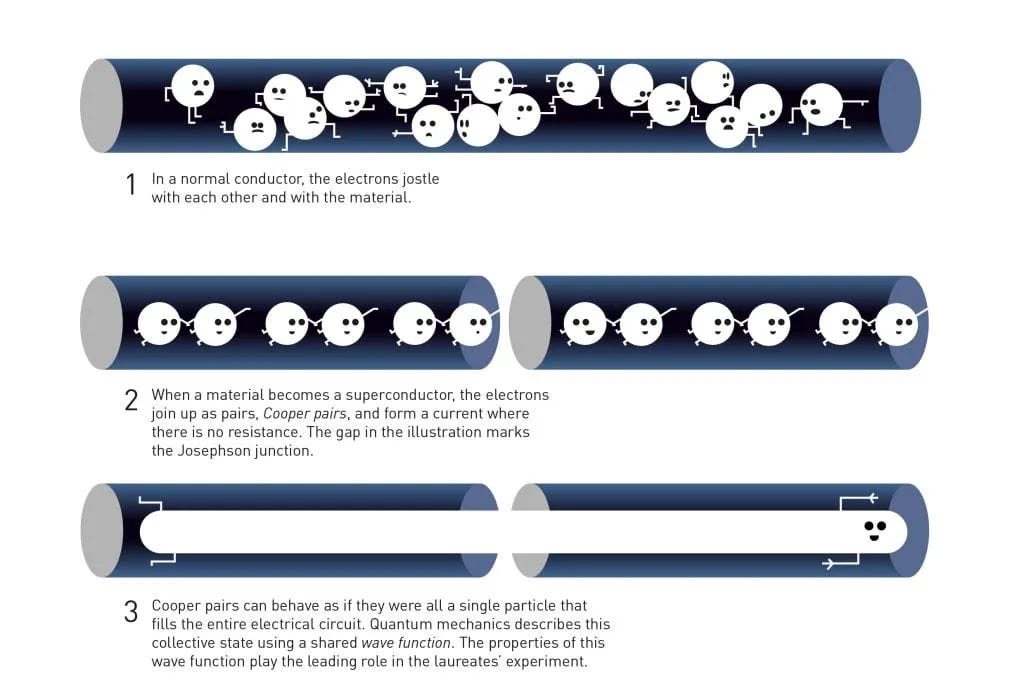

Bosons (The Socialites): Named after Indian physicist Satyendra Nath Bose, these have integer spins and symmetric wavefunctions. Bosons love to pile up in the same state, which is how lasers and superconductors work.

Examples: All gauge bosons (photon, gluon, W&Z bosons) and the Higgs boson.

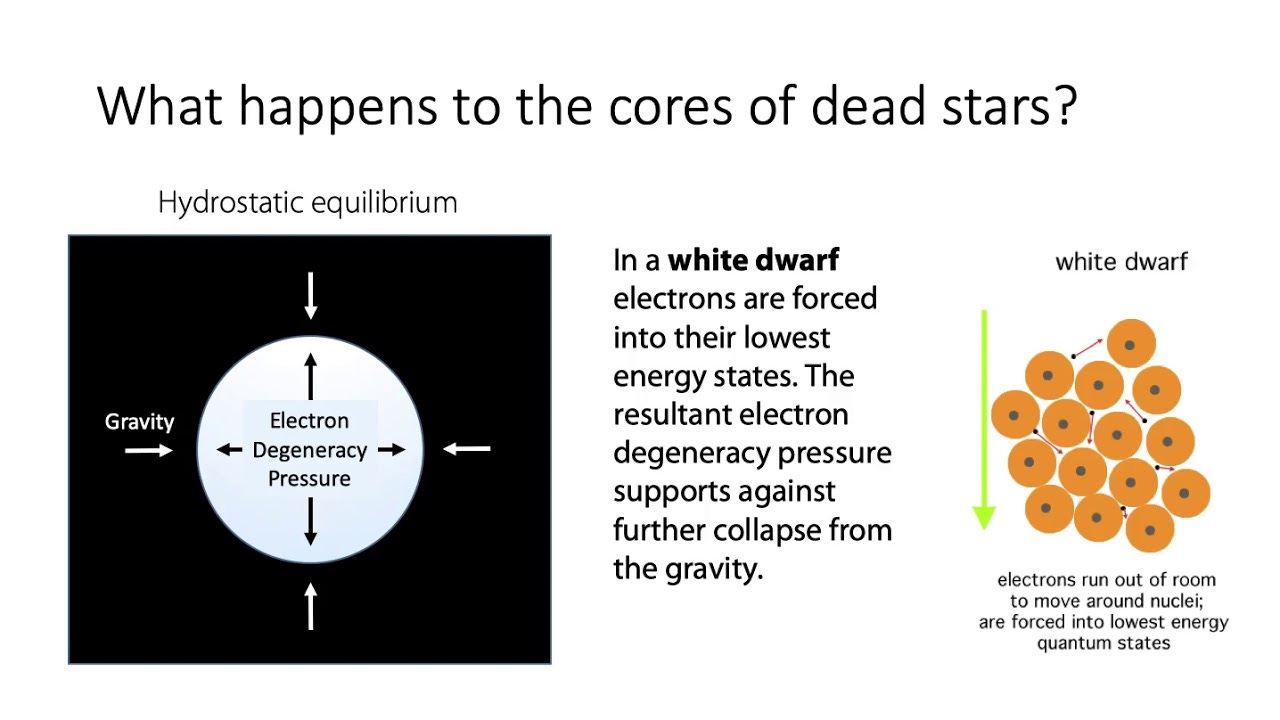

Fermions (The Hermits): Named after American physicist Enrico Fermi, these have half-integer spins and antisymmetric wavefunctions. They follow the Pauli Exclusion Principle, which states that no two fermions can occupy the same “seat” at the same time. This “antisocial” behavior is why matter is solid; it prevents all the electrons in an atom from collapsing into the center.

Examples: electron, quarks (which make up protons and neutrons).

Why should a particle’s spin dictate its statistics?

In basic quantum mechanics, there’s no obvious reason. You could theoretically imagine a “spin-1/2 boson” on paper. In QFT, however, the rules of special relativity (specifically causality and locality) enforce this spin-statistics connection to preserve the mathematics.

I won’t explain it through the maths of QFT and relativity though. It’s beyond the scope of our discussion. Instead, let's understand it visually.Rotating a particle 360° creates a loop in space-time. Exchanging two particles is also a kind of loop: if you move Particle A to B’s spot and B to A’s spot, you’ve traced out a path that looks very much like a rotation.

The video conveys this idea beautifully.

Mathematically, a 360° rotation and a particle exchange are deeply related.

If a particle flips its sign when rotated (half-integer spin), it must also flip its sign when swapped (fermion).

If it stays the same when rotated (integer spin), it must stay the same when swapped (boson).

The algebraic rules of quantum mechanics must fit together consistently. If you tried to put two fermions in the same quantum state, the antisymmetry of the wave function forces it to cancel itself, leaving zero probability for that configuration. This proves that two fermions can’t exist in the same quantum state, also known as the Pauli exclusion principle. The principle is a consequence of the Spin-Statistics theorem, which is the universe’s way of ensuring that the math of turning (spin) and the math of swapping (exchange symmetry) never contradict each other.

A Note:

Fermions and bosons are the only kinds of elementary particles seen in 3D. In 2D systems, however, another class of particles exist, known as the anyons. This is not relevant to our discussion, but worth mentioning for your further study.Experimental Signature

The sign flip of a spinor is very real and can be measured. In precision experiments using neutron interferometry, physicists split a beam of neutrons into two paths. They rotated the neutrons in one path by 360° and then recombined them with the other path.

If the rotation did nothing, the two paths would perfectly align. But instead, the paths canceled each other out. The 360° turn had flipped the sign, creating “destructive interference.” It took a full 720° turn to bring the patterns back into alignment.

Why does this matter?

Without this abstract link between rotation and swapping, the universe would be a featureless soup. The consequences of the Spin-Statistics Theorem are written into the very fabric of existence.

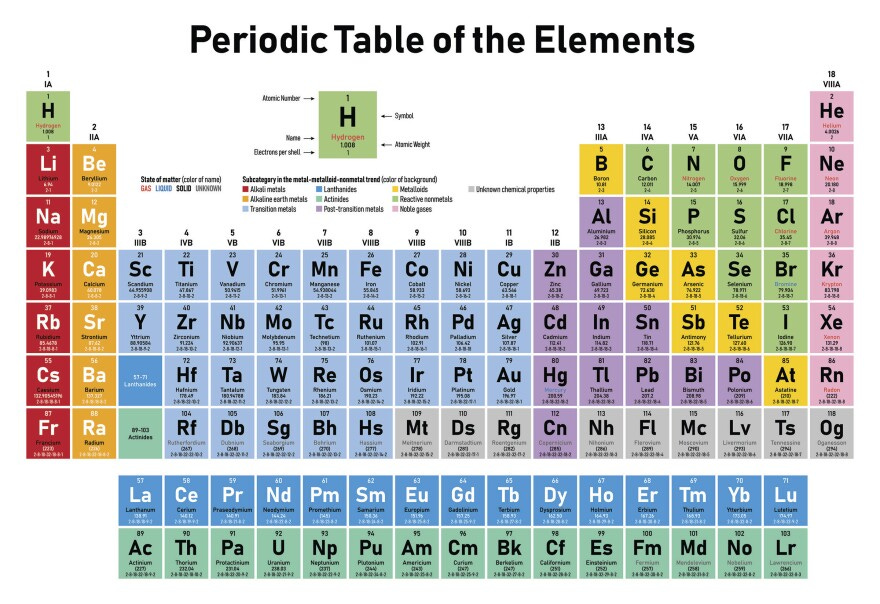

Chemistry: Because electrons, protons, and neutrons are fermions, they stack into shells rather than collapsing into the center of the atom. This creates the Periodic Table and allows chemical bonding. If they were bosons, every atom would behave the same way, complex molecules would never form, and life would be impossible.

The periodic table (Image Credit: stock.adobe.com). Link Superconductivity: In certain materials, at very low temperatures, electrons (fermions) pair up to form “Cooper Pairs.” These pairs act like composite bosons, allowing electricity to flow with zero resistance.

The Fate of Stars: In White Dwarfs, gravity tries to crush matter into a point. But the electrons, being fermions, resist being squeezed into the same state. This “Degeneracy Pressure” is the only thing stopping the star from collapsing into a black hole.

To Summarize…

In QFT, the universe is incredibly constrained. Marrying the laws of quantum mechanics and relativity leaves the universe with very little “wiggle room.”

Spin tells you how an individual object behaves when it turns.

Statistics tells you how a crowd of objects behaves when they swap.

This elegant, inevitable pairing is the reason you are sitting still in your chair, and every star out there is shining. Once you see the link, the architecture of the universe stops looking like a collection of random facts and starts looking like a single, beautifully coherent masterpiece.

Next Time…

Until now, we’ve built a universe of fields, but a universe where fields don’t talk is a dead one. For stars to shine and atoms to hold together, these fields must interact. So next time, we answer the question:

Why do fields talk, and how do they do it?